There are 32 agencies that submit license plate reader data to the Northern California Regional Intelligence Center (NCRIC), the regional fusion center for Northern California. However, many more agencies are able to access that data once it has been sent to the NCRIC.

According to records received in response to a public records request, 71 agencies queried the NCRIC license plate database between February 21 and March 21, 2021. While the agencies looking up license plates at the NCRIC are generally law enforcement agencies located in Northern California, a few of these agencies may stand out as somewhat unusual. The United States Department of Agriculture Office of Inspector General had the 11th highest number of queries to the license plate reader database. Other agencies included the National Park Service, the California Department of Motor Vehicles, and the US Postal Inspection Service.

Other agencies accessing NCRIC’s license plate reader database are to be expected, such as the police departments from the Bay Area’s three largest cities: San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland. After the three biggest users of the NCRIC license plate reader database, the users vary from Fremont, with an estimated population of 240,000, to cities like Dixon and Atherton, with populations of less than 20,000.

Piedmont, with more than 39 automated license plate readers situated at the border with Oakland, has been one of the three largest submitters of license plate reader data to NCRIC, with 22 million images of vehicles of license plates and vehicles annually. However, during the period from February 21 to March 21, 2021, it didn’t use the NCRIC license plate reader database even once. Vallejo, which submits more than 15 million images of vehicles of license plates and vehicles to NCRIC annually, queried NCRIC’s database just four times in this one month period. Berkeley, which doesn’t submit any license plate reader data to NCRIC, queried the database 61 times during this one month period.

According to records for October 2021, Piedmont queried the NCRIC license plate reader database just once while Vallejo didn’t query the database at all.

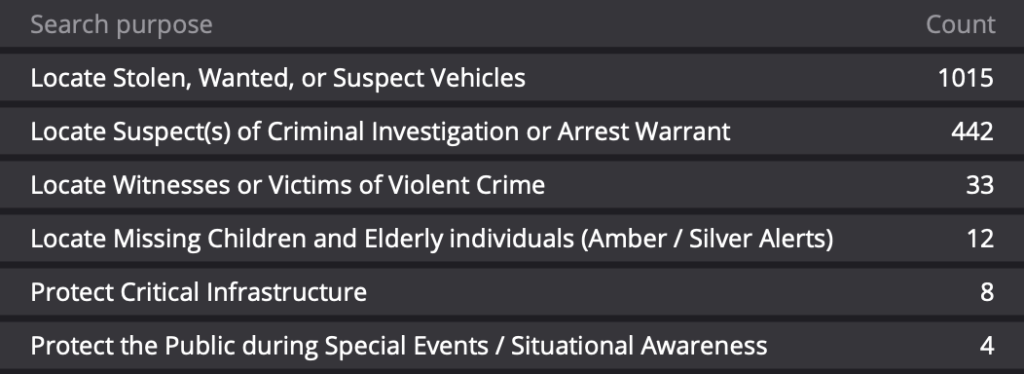

A table showing the agencies and the number of queries to the NCRIC license plate reader database for 2/21/21 to 3/21/21 is shown below. Note that queries by a District Attorney’s office may be included for some of the agencies listed, like the San Mateo, Alameda and Solano County Sheriffs. In addition, Danville, which is listed below, is contracting out its policing to the Contra Costa County Sheriff.

| Agency | Count |

| San Francisco PD | 650 |

| Oakland PD | 277 |

| San Jose PD | 230 |

| Fremont PD | 88 |

| San Mateo Co. Sheriff | 73 |

| San Leandro PD | 66 |

| FBI | 63 |

| Berkeley PD | 61 |

| California Highway Patrol | 69 |

| East Bay Parks PD | 57 |

| USDA OIG | 51 |

| South San Francisco PD | 46 |

| Hayward PD | 31 |

| Newark PD | 30 |

| Dixon PD | 30 |

| Marina PD | 27 |

| Alameda Co. Sheriff | 26 |

| NCRIC | 26 |

| Redwood City PD | 26 |

| Palo Alto PD | 24 |

| Milpitas PD | 19 |

| National Park Service | 18 |

| Chico PD | 26 |

| CA DMV | 14 |

| Sunnyvale DPS | 14 |

| Belmont PD | 12 |

| Napa PD | 12 |

| Napa Co. Sheriff | 13 |

| Monterey PD | 10 |

| Santa Clara Co. Sheriff | 9 |

| FBI IC | 9 |

| Santa Rosa PD | 8 |

| Daly City PD | 8 |

| Menlo Park PD | 8 |

| Hercules PD | 8 |

| Atherton PD | 8 |

| Colma PD | 7 |

| Vacaville PD | 7 |

| San Mateo PD | 8 |

| Burlingame PD | 6 |

| Novato PD | 6 |

| Santa Clara District Attorney | 5 |

| Antioch PD | 5 |

| Morgan Hill PD | 5 |

| Solano Co. Sheriff | 5 |

| Union City PD | 4 |

| Dept. of Homeland Security | 4 |

| CA Dept. of Justice | 4 |

| Santa Clara PD | 4 |

| US Postal Inspection Service | 4 |

| Conta Costa Co. Sheriff | 4 |

| Benicia PD | 4 |

| Vallejo PD | 4 |

| Mountain View PD | 4 |

| Stanislaus Co. Sheriff | 3 |

| Hillsborough PD | 3 |

| Pleasant Hill PD | 3 |

| Livermore PD | 3 |

| Santa Cruz Co. Sheriff | 3 |

| Foster City PD | 2 |

| Seaside PD | 2 |

| Contra Costa Co. DA | 2 |

| Rocklin PD | 2 |

| US Dept. of Justice | 2 |

| Pacifica PD | 2 |

| Richmond PD | 1 |

| Sacramento Co. Sheriff | 1 |

| San Bruno PD | 1 |

| Tracy PD | 1 |

| Central Marin PD | 1 |

| Danville PD | 1 |

The Vallejo Police Department already has a network of license plate readers in locations around the city. Two of Vallejo’s ALPRs can be found on

The Vallejo Police Department already has a network of license plate readers in locations around the city. Two of Vallejo’s ALPRs can be found on